Excerpt from the book “Pairings of spanish wines with exotic cuisines”.

Click to see the preparation of these dishes, in American recipes or Asian recipes.

Salutation

Spanish wine has moved from the Middle Ages to the century of nanotechnology in a little more than two decades. This has led to a revolution for consumers, who have discovered that wine not only smells like wine but that there are thousands of hues, even radically different flavours, between a classic Rioja and a new-generation one, or between a white wine from Verdejo grapes and one from Albariño, Chardonnay, Godello, Sauvignon blanc, or Treixadura. There is even a great difference between a young Ribeiro and another one which has been fermented in barrels on its lees.

Exotic cuisines

How could we define this concept? Quite simple: Japanese cuisine is exotic for a Spanish person and Spanish cuisine is exotic for a Japanese person.

There is a geographical proximity factor which influences the degree of exoticism, but it is actually the cultural factor which makes the difference. Take for instance that example about Spain and Japan: both are prime examples of fish-eating countries, and rice dishes are common in both of them, but compare some cod ‘al pilpil’ with a tuna sashimi, or a Valencian paella with sushi and you will see two opposite worlds, two radically different cultures, two ways of thinking and understanding cooking with nothing to do with each other. That is culinary exoticism.

What about Chilean cuisine? Apart from the fact that its roots are clearly Spanish, the Southern Cone countries have their own personality and we could speak about some dishes such as the ‘ají de gallina’, the ‘chupe de camarones’ or the Chilean casserole, but both Chile and Argentina are large wine-producing countries so it seems impossible for our wines to make their way in these markets. Those are walled gardens, just the same as France or Italy. Our wines would make unforgettable pairings with those cuisines, but there is some patriotic pride that clouds people’s judgement, Not all of us share that view –I love a good Burgundy or a reserve Barolo, even a good number of Chilean and Argentinean wines- but we have to admit that commerce has gates and there is no point in swimming against the current, especially when there are emerging markets which can be amazed by our wines.

Why only America and Asia? As a matter of fact, one of the most fascinating culinary ranges is the Mediterranean, with common or closely related roots but with a very different evolution, for example, between the Magreb cuisines and those from the Middle or Mediterranean East, that is, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Israel, even Turkey. Those are really exotic flavours that we find shocking and stunning, but Spanish wine-makers do not give those markets a chance. Why? Really, I don’t know. It might be because of Islamic radicalism, which bans alcohol consumption –the Koran doesn’t say anything about this, but the Taliban do-, or because they are relatively poor countries, or because France and Italy had made their way into these markets long before we started exporting.

There are no African countries, either, due to the same reasons to a great extent, mainly to the poverty of their people -dictators and exploiters do have colossal fortunes but they are more likely to drink Champagne and great “crus” from Burgundy and Bordeaux- and the fact that they have a large-scale wine producing country, South Africa,.

What about Australia? Well, apart from producing a great amount of wine –they expect to lead the world market before 2025-, the problem is that they do not have a cuisine of their own. They eat, sure, but they have Chinese cuisine for the Chinese, Dutch cuisine for the Dutch, British cuisine for the British and Hindu cuisine for the Hindu.

Having explained the boundaries of this book, let’s move on to other interesting details.

Other tables, other customs

You may remember that unbearable American TV series from the eighties called “Falcon Crest”, which was so successful that provoked some ‘cabernetmania’ in Spain. Before that, American actors used to drink only whisky, milk and Coca-Cola, but the nascent Californian wine industry imposed its pressures and, since then, they have drunk wine, reaching ecstasy with that cute little film called Sideways, which has made people adore Pinot Noir wines from 2004.

Wine culture has got into the USA hand in hand with the film industry, which deserves our applause, not only for the outstanding increase in wine consumption achieved in this country but also in all its followers, which means half the world.

We have got used to seeing the characters in a series come home and open a bottle of Chardonnay or dine in an elegant dining-room with a beautiful ruby red wine, but the underlying message gets through. Either in Mexico, India or Japan, upscale restaurants usually place a gleaming bottle of wine on each table.

Wine has become fashionable as a sign of Western elegance and its consumption in emerging countries has tripled this century, but the most important thing is that all the indicators signal that it is not a passing wave for consumers but a matter of checking its gastronomic qualities and getting the taste used to new flavours. All this, together with the nutritional benefits of wine that have been reported to the detriment of other distilled beverages, makes us think that wine drinking is getting as customary as in Europe, where it is part of our usual diet.

The game is already on and we know what is at stake: billions of euros, dollars, rupees, yens, pesos… Globalization, and the consequent irruption of TV series into the lives of citizens who see their admired stars fashionably drink a glass of Sauvignon while debating, has accomplished the miracle. But not only Spain makes wine. Wine makers must learn to study each case, since the conditioning factors are different from Seville to Singapur and the fight is relentless.

Spanish wine around the world

There is an old saying: “What you sow is what you reap”, and little or nothing has been sown in Spain. Except for a few notable exceptions, national winemakers have been satisfied with the domestic market, crossing our borders just to compete in price with the worst wines from Algeria, Argentina or South Africa, and never outside Europe.

Meanwhile, France had been planting their flag all around the world as a sign of quality and distinction. More or less successfully, from Moscow to San Francisco, from Hong Kong to New York or Delhi, wine meant France, either Champagne or Burgundy. The seeds had been sown, ready to sprout and flood the best tables in any country where money was made. That happened when that great communication monster called Hollywood exchanged whisky for wine in their films. The whole world assumed that sign of refinement and even the Japanese have stopped imitating cowboys and started celebrating their comeback home with a glass of Chardonnay. The world already drinks wine, but just French and American. Now it is our time to sow or we will reap nothing.

As I have already explained, quality wine was not produced in our country until the last decades of the 20th century, so we must analyze this market as new, forgetting the secular winemaking tradition of many villages and families that many winemakers boast of.

In the eighties, most Spanish wines couldn’t compete in international markets due to their low quality levels. Hardly a dozen wineries considered exportation as an important part of their marketing policies. Most exported wine was just bulk wine sold to France or Italy, were it was reformed and commercialized under their own brands. Spain did not exist in the world of wine.

From the 1990s onwards, new technologies appeared and wine started to be produced with quality criteria. Production per vine was reduced to improve the musts, harvesting was cared to avoid uncontrolled fermentation, computer-assisted cold maceration in stainless steel vats with cooling jackets was used, even local varieties apparently disappeared could be recovered through modern DNA control techniques.

Wine became fashionable, not as a sign of snobbishness as some said but because there were real quality wines, and specialized media spread the news and started educating consumers.

Then the situation became uncontrolled. Vines were planted everywhere. Spain was flooded with wine that had to be disposed of, so exportation started, this time with acceptable, even high quality wines.

The 21st century marked the birth of Spanish wine in the world, but, as it usually happens in this country, chaotically, without planning or joint strategies. Here we are, in a quagmire that can end in tragedy. A winemaker friend of mine told me once: “Look Pepe, this pallet of Rioja wine is going to Germany. This is my wine, 95/100 points Proensa classification. 20€ a bottle. And this other one, 2€ a bottle. How can this be assimilated?”

We are raising our heads in a very competitive new world where the rivals have sophisticated weapons. We are not going to win battles with sticks.

The worst thing is that there are institutions with huge budgets that sh

ould be planning and organizing the wine sector, but they just devote to “navel-gazing”, doing official politics, protecting their positions and spending public money in self-complacency fairs to justify expensive trips which are worth nothing for the targets that should have been set.

Spanish wine list

Spanish consumers, and mainly caterers, should be taught that winemaking Spain does not end in Cantabria, I mean, there are good wines outside Rioja and Albariño grape. However, this ha

s been so often repeated and of so little benefit that I won’t waste my time teaching them here. Instead, I will write for readers from other countries, who are surely more interested in learning about our wines than those waiters that buy sale verdejo wines from Rueda at less than one euro a bottle.

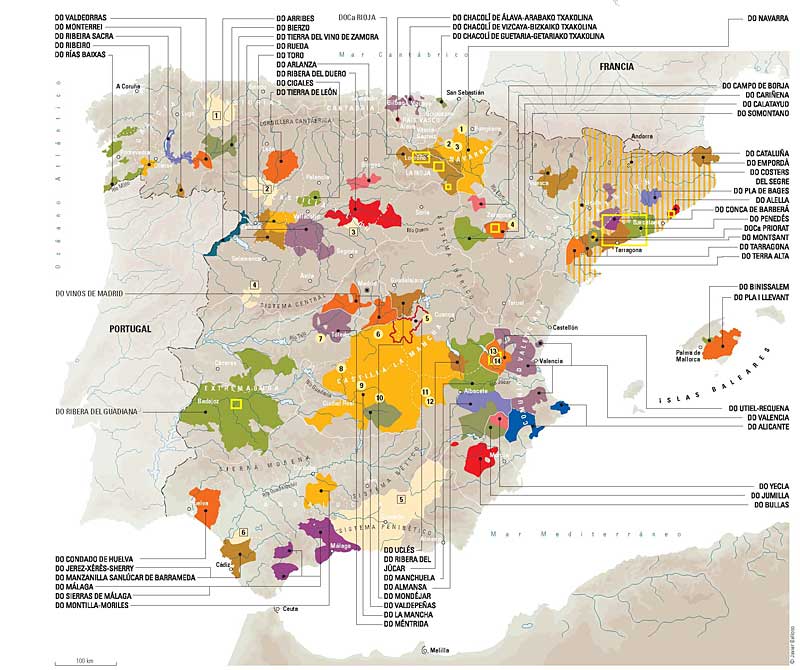

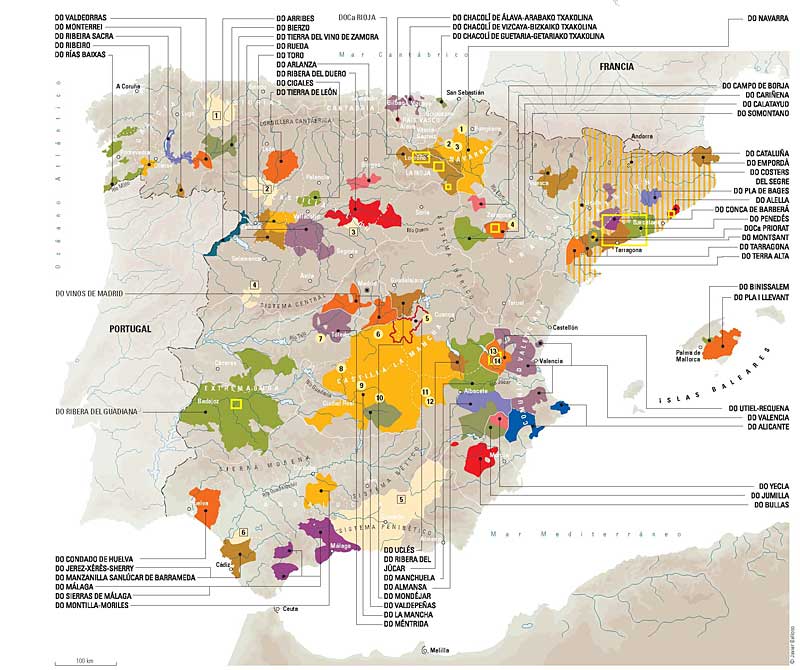

Spain is a country of contrasts, like France and Italy, perhaps more than them. From a geographical point of view, flat arid areas can be found together with green mountain regions, with a climatic diversity from temperate climates by the sea to continental highlands over 700 m. above sea level. Furthermore, lithological maps show clay terrains together with calcareous or granitic soils and flood plains. All that multiform mosaic results in an endless variety of wines that keep the particularities from their terroir and grapes.

From an ampelographic point of view, the grapes called Tempranillo, Tinto Fino, Ull de Llebre, Cencibel, tinta aragonesa, Arganda and escobera are the same –and so is Tinta de Toro, according to “El Encín”, Vine Germplasm Bank of the I.M.I.A. (Agricultural Research Institute of Madrid). However, the influence of each terroir is so strong that their wines are radically different, as we can check in crianzas from Rioja, Ribera del Duero, Toro or La Mancha.

Broadly speaking, Spain can be physically described as a large square peninsula, formed by a large plateau with several mountain ranges, protected from the north by the Cantabrian Mountains and the Pyrenees, and surrounded by more than 8000 kms. of coastline, the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean and Cantabrian seas.

According to those characteristics, we can distinguish between coastal wines, produced in temperate, wet, climates, and inland wines, produced in areas with extreme temperatures and low rainfall. Wines from the northern Atlantic coast (Galicia) are different from the southern ones (Jerez), and also different from the Mediterranean.

I cannot list, much less describe, the grape varieties that are grown in Spain –they are more than 200. If we take into account the different ways of winemaking, the number of wine types could be over 1000; as I have said, it is a fascinating mosaic whose variety and richness of aromas and tastes can make you lose your mind.

This book offers a small but selected sample of the most interesting profiles that can be found in other continents’ markets. It is a pity that many have “missed the boat”, believing that “good wine needs no bush”. One of the most important examples missing is sherry, victim of the apathy of some winemakers who continue to see the world from their horses’ back, despising the ground that supports them.

Despite the blindness of whole regions, you will find great reds, scented whites and refreshing cavas in this selection. The wine list is short but varied enough to pair with the most sophisticated dishes from all the cuisines in the world –we also have rosé wines, but winemakers do not seem interested in promoting them.

The missing ones

In the first place, I must make clear that this book is not a wine guide, nor a vademecum. The number of brands, or wines, existing in Spain has been estimated in 7000, the most exhaustive guide lists about 4000, and our books include just about fifty.

Our target is to bring Spanish wines closer to foreign palates, showing, for example, how an Albariño wine can go very well with such an American dish as BBQ ribs. That is the purpose of our collection: opening your mind to one of the most educated hedonistic pleasures known. Eating is not the same as tasting, and the science of pairing is the implementation par excellence of sensory analysis.

There are many wines missing, excellent and well-known, but we can only invite, not force, wineries to take part in this work. The current economic crisis has made many companies reduce their expenses to unbelievable extents. It is the same as if a truck driver stopped buying petrol for his truck. He would save a lot of money but be condemned to death.

We would have liked to include all of the seventy denominations of origin that there are in Spanish wine, at least one wine from each, but the Regulatory Councils’ incompetence and idleness –even rudeness in many cases- have made that task impossible. Many small wineries export their wines in an uncontrolled way, bargaining over them as in a flea market to get some profit. They do not know about wine culture or pairing, their only aim is to sell a batch of wine at any price, and they do not mind if it is relabelled.

At this crucial moment for the development of Spanish wine, when exportation must be the support that provides stability to our products, our Denominations of Origin keep sponsoring the local football team, the bicycle tour or the visit by some showgirl to allow the president take a picture with her and boast about it while having a glass of wine in the village pub.

None of that matters to our readers from Tokio, Hong Kong, Puebla or Washington. It is up to us if the world of Spanish wine is a brothel, but I have to explain the important gaps in our selection. Wines from Jerez, Priorato, Valdeorras, Somontano, Txacolí and so on could disappear before millions of consumers have had the opportunity to try those wines, those varieties, such as the Godello grape, for which we bet so much since its origins. Certain regions such as Navarra, which seemed launched on the international market, have buried their heads in the sand because of the crisis, letting themselves die.

Let’s hope this will result in a clarification of the spectrum of Spanish wine, reducing those 7000 brands by half so that the winemakers who fight for doing things well do not get obstructed by the mediocre.

Stereotypes or old pairings

We can no longer speak of classic pairings. Those thousands boards we can find on the internet giving advice on what wine goes better with each particular dish have become so outdated that they could be considered as an insult to good habits.

In my first book about pairings, Comer con vino, awarded with several international prizes, such as the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards 2009 and the Best Book on Matching Food and Wine of the World, I quoted a list of the most relevant classic pairings of the moment, like that by Andrés Proensa, the maximum authority in the field of wine in Spain, an outstanding guide that detailed each type of food and what wine profile could accompany it most successfully. I think it was good advice for those wishing to know the basis of pairing, but from that time forward many crazy theories have appeared, like the so-called “molecular sommellerie” which many gastronomic illiterates consider a scientific method. There are multicoloured boards in which an infographist pontificates on what wine must accompany meat, disregarding whether it is pork or beef, whether it is grilled or boiled with vegetables, or whether the wine is young or vintage. That is like saying that all blondes are dumb or all Chinese people look alike –I even read that wines from Garnacha grapes are light on one of those boards!

I regard those banalities as a crime against wine culture. In more than thirty years doing research in this field I have found surprises that defied the basic principles of pairing, even more when preparing this book as it deals with very complex flavours in which the raw material can be overridden by the aromas and tastes from preparation. For example, prawn Pad Thai went outstandingly well with Ramón Bilbao, a red crianza (vintage) from La Rioja.

In order to enjoy exotic cuisines, we must put away stereotypes because these dishes were created to be accompanied by tea, beer, spirits or soft drinks, and pairing them with wine requires absolute eclecticism. The most nonsensical, most inconceivable combinations must be tried to find such brilliant harmonies as those BBQ ribs with a delicate albariño by Santiago Ruiz. This combination will be unforgettable for anyone who tries it, no matter if it is a diner from Idaho who has never heard of Albariño grape or of San Miguel de Tabagón, a village in Rías Baixas in Pontevedra, more than 8000 kilometres away.

One must not speak about what one does not know. I have found very ridiculous advice, like that by a self-called sommelier from Guatemala who has declared Antigua “Pairing Capital” for the months of October, November, December and January, in a country where you have to explain concepts like “the areas of land where grapes are grown are called vineyards” or “the fermentation process is essential in the creation and preparation of this beverage”… Please, be more serious. One thing is fashion and a very different one to go out to the streets in a thong.

Troublesome products

In countries like Mexico, India or Thailand there are a lot of recipes full of aromatic and spicy herbs, barriers that strongly condition the analyst’s work, as each product has its own competences and incompatibilities. Indian curry sauce, Mexican mole or a Thai dish like Pad Thai have such penetrating and intense tastes that very few wines can withstand that storm. But some can, and the resulting harmonies are outstanding, mainly if we understand that one of the main functions of wine at the table is to balance the sensations in our mouths.

The winemakers themselves have sometimes told us that they had especially enjoyed their wines with a particular dish. Two unexpected pairings were suggested by Luis Delgado and Nacho Arzuaga respectively: Hamachi Kama with Astrales and Huajapan mole with Arzuaga. There are no fixed rules in this world of gastronomic harmonies. I would have never tried a grilled fish collar with such a huge wine as Astrales, or ordered a great Ribera de Duero with such a strong dish as mole, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating and this job is always surprising.

Cooking and “molecular sommellerie” demiurges establish “scientific” links that, in practice, show their lack of honesty because they do not work at all, no matter how much they insist that ginger has got molecules of citral in it and must consequently be accompanied by red Garnacha wine from Cariñena.

Some general principles are right in most cases, for example Albariño wines will go well with poultry and boiled pork dishes (that is a classic pairing in Alsace and along the French-German border, mainly in Bavaria). We also know that game meat dishes require vintage red wines. However, pairings must be checked one by one, because great surprises can be found. I have found that barnacles (and other seafood, I found out later) are a perfect combination with Rioja gran reserva (60 months ageing). I have recently read an interesting theory about this, based on the behaviour of tannins. In fact, great consumers of barnacles –from Galicia, of course- advise eating them with red wine, a good vintage Rioja if possible.

Nevertheless, these rules are valid for traditional Spanish cuisine, a somehow simple cooking in which the primary tastes from the main products are carefully preserved, but when we approach cuisines that use such an abundance of sophisticated products no previous criteria can be established, since we cannot know if the flavour of the dish will come from the beef that names the dish or from the taste of oyster sauce, coconut milk or tamarind puree.

We have selected conventional dishes in popular cooking from the countries studied. Sukiyaki may not be the most dazzling dish in Japanese cuisine, but it will be in the menu of any Japanese restaurant, mainly in Europe or America.

When we were preparing this book, we conducted a lot of prior tests with some of the potentially most troublesome products, such as capsicum (the spicy element in red chilli peppers), ginger, wasabi, sweet-and-sour sauces, soya sauce, mole, curry or chutney. We made a little supporting manual for each case with very interesting conclusions, thinking that it would be helpful for field work but it was not. The cloud of tastes, aromas and sensations that each dish involves just calls for leaving the mind blank and allowing the global sensation to guide us in the right direction. And, of course, try, try and try.

Some day intelligent computers will be available; then they might be connected to a state-of-the-art gas chromatograph to predict acceptable pairings. Until then, however, only the tasters’ senses can determine if a red tuna sashimi goes better with a Verdejo wine or with a Ribera de Duero crianza, as our analysis actually determines.

Molecular sommellerie

I feel somehow compelled to refer to this new fashion because there are some “experts” who have taken a master in Marketing in Harvard to run daddy’s winery and, since they have also attended a “molecular sommellerie” course in London, despise old tasters who have been working and studying this complex field for decades.

In brief, this is the story.

During the 1980s, the work of professional wine tasters was questioned because some very sophisticated devices called “gas chromatographs” irrupted in the world of Spanish wine. They could analyse the products tested to unbelievable extents. It was said that no taster could perceive the presence of ethyl hexanoate in a glass of white wine. That was right, we could not, but we did perceive the aroma of fresh green apples. Today, we know that it is a substance derived from the lipid metabolism of yeasts and that the aroma of apples is actually due to about 400 substances, mainly “impact compounds”, in this case butyl acetate, 2-methylbuthyl acetate and hexyl acetate.

Is the chromatograph of any use? It is obvious that it is. It must be considered an essential tool in any oenological laboratory, but not to taste wine but to analyze certain defects, illegal additions or deviations in the features of a particular variety. A Rolls-Royce is an outstanding, elegant, comfortable, beautiful car, but it is of no use on forest roads or desert dunes, simply because those are not its functions.

Very soon it became clear that laboratory analysis could not replace sensory analysis, nor could chromatographs replace tasters, since those were two different research fields, complementary, not competitive.

But suddenly in 2009 a Canadian sommelier, François Chartier, taking advantage of the fashion for “molecular cooking” invented by Hervé This and Pierre Gagnaire, jumped on the eccentricities bandwagon and produced what he called “food harmony and molecular sommellerie”. He proclaimed himself “harmony’s creator” and invented a supposed scientific world in which, for example, on the basis of a volatile compound as menthol, he established links between a dozen vegetables and several wines that could contain aromas of that kind.

I do not really consider worth mentioning this waiter in this book, but he has been able to manage mass media to involve other actors like Ferrán Adriá in his show. As a result, he is travelling around the world lecturing, giving master classes, publishing best-selling books, even labelling wines as his own under the title “La nouvelle gamme de vins signée Chartier, Créateur d’harmonies” and mainly misleading those marketing geniuses that are now running Spanish wineries. I would like to ask a real winemaker his opinion about some ideas by that sommelier/waiter, like adding toasted fenugreek seeds to a Jerez fino or manzanilla to get an evolved wine like those popular in Ancient Rome: “Inspiré par les romains, et signé François Chartier”. Awesome, isn’t it?

Aromatic parallelisms between a wine and a dish only indicate that they must not be served together, because one will overshadow the other. For example, if a Godello wine fermented on its lees smells of ripe apple, we cannot serve it with a dish containing applesauce, because the intensity of the dish will overshadow the subtle aromas from the wine and that slight memory of ripe apple will not be perceived.

Balancing the mouth

One of the main functions of wine in pairing is to balance the mouth after some food bites.

If we eat chilli con carne, with such hot tastes as spices, the sweetness from mole, the meat fat and the starch from the beans, our mouth will get hot and call for something to refresh it. As a consequence, although the aromatic spectrum could make us think that a red wine is advisable, we should actually choose a fruity dry white wine like that albariño Lagar de Cervera that we are proposing.

In previous books I have already explained the difference between the warmth of dishes and their temper, but I will repeat the explanation in brief because it is an essential concept when dealing with these dishes.

My first book “Comer con vino” mentioned a parallel between the temperature of dishes and light intensity in photographic cameras. Intensity is measured in luxes and temperature in degrees Kelvin. A photograph can have low light and need slow shutter speed and maximum diaphragm aperture, but in spite of that it can be bluish because the temperature is high (sunlight), or, on the contrary, it can have high light intensity and low temperature (halogen lights).

It is often the same with food. A herring salad with beet and cream sauce may be served cold, but it will have warm, sweet, cloying tastes, so it will call for a fresh wine, usually a white. On the contrary, veal in oyster sauce will be served very hot but its temper will be cold because the ingredients are, so it will call for a warm wine as the one we have chosen for it, Cruz de Alba, a vintage red from Ribera de Duero with ripe fruit and vanilla tones of toasted wood, almost moreish, a velvet that will comfort our mouth.

These paradoxes frequently happen with seafood, even with many fish dishes. For example, red tuna sushi has got both cold temperature and cold temper, so we advise accompanying it with another great Ribera de Duero, Abadía de San Quirce, a wine that, when taken in mouth after each bite, seems to be part of a ritual because it rounds out the tactile sensations in our mouth, preparing us for another bite.

On the contrary, sweet and sour pork is a warm and hot dish that calls for some refreshment, so we accompany it with a very fresh fruity albariño, Fulget, which will temper and clean the mouth, leaving a delicious memory of green apples and inviting us to go on tasting the dish.

But anyway, all that will be told in the following pages.